|

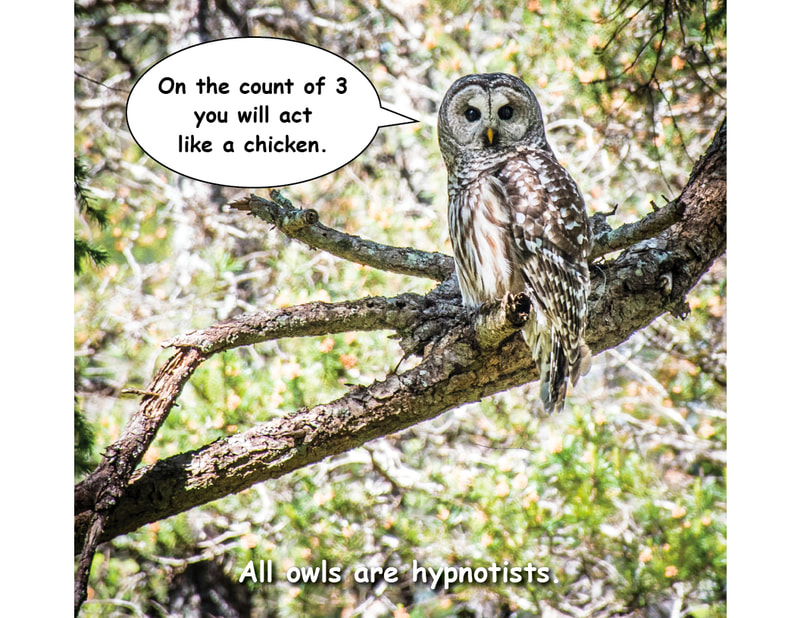

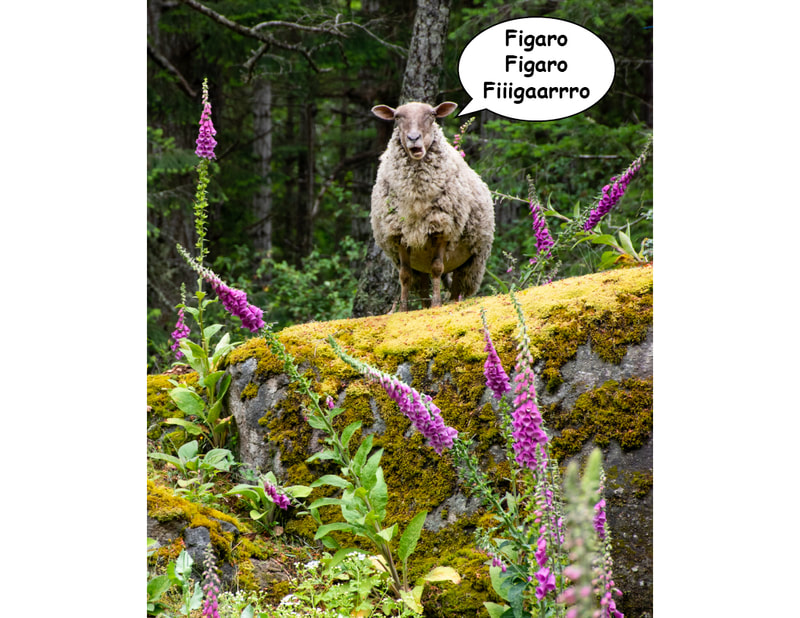

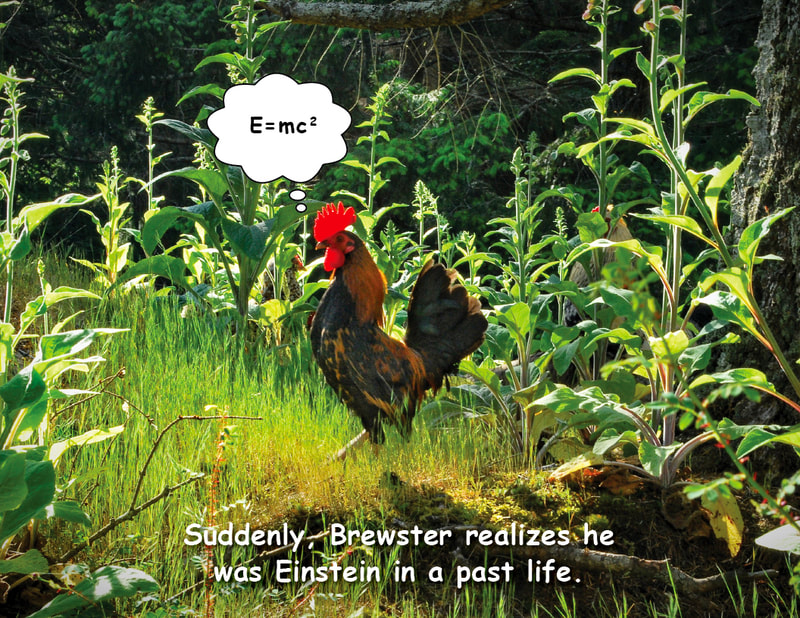

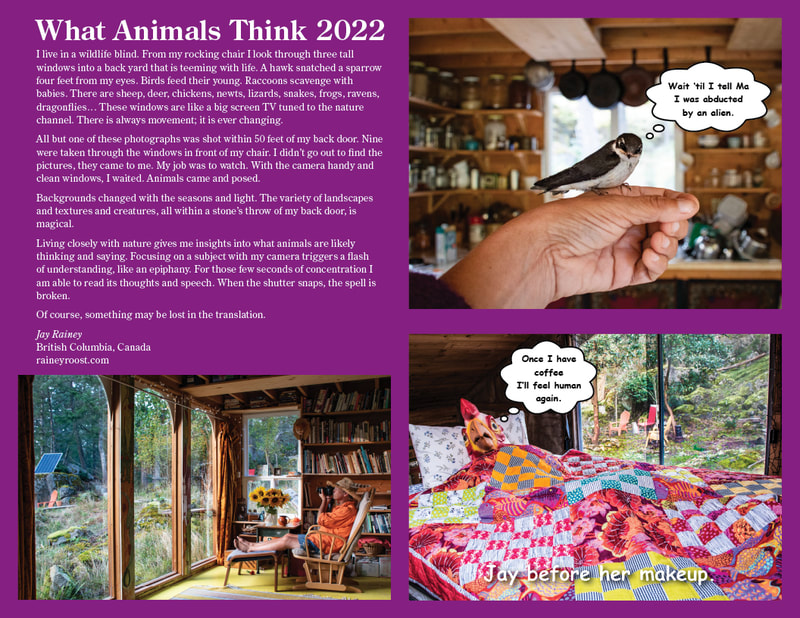

I live in a wildlife blind. From my rocking chair I look through three tall windows into a back yard that is teeming with life. A hawk snatched a sparrow four feet from my eyes. Birds feed their young. Raccoons scavenge with babies. There are sheep, deer, chickens, newts, lizards, snakes, frogs, ravens, dragonflies… These windows are like a big screen TV tuned to the nature channel. There is always movement; it is ever changing. All but one of these photographs was shot within 50 feet of my back door. Nine were taken through the windows in front of my chair. I didn’t go out to find the pictures, they came to me. My job was to watch. With the camera handy and clean windows, I waited. Animals came and posed. Backgrounds changed with the seasons and light. The variety of landscapes and textures and creatures, all within a stone’s throw of my back door, is magical. Living closely with nature gives me insights into what animals are likely thinking and saying. Focusing on a subject with my camera triggers a flash of understanding, like an epiphany. For those few seconds of concentration I am able to read its thoughts and speech. When the shutter snaps, the spell is broken. Of course, something may be lost in the translation. To order this calendar email me: [email protected] $20 each.

0 Comments

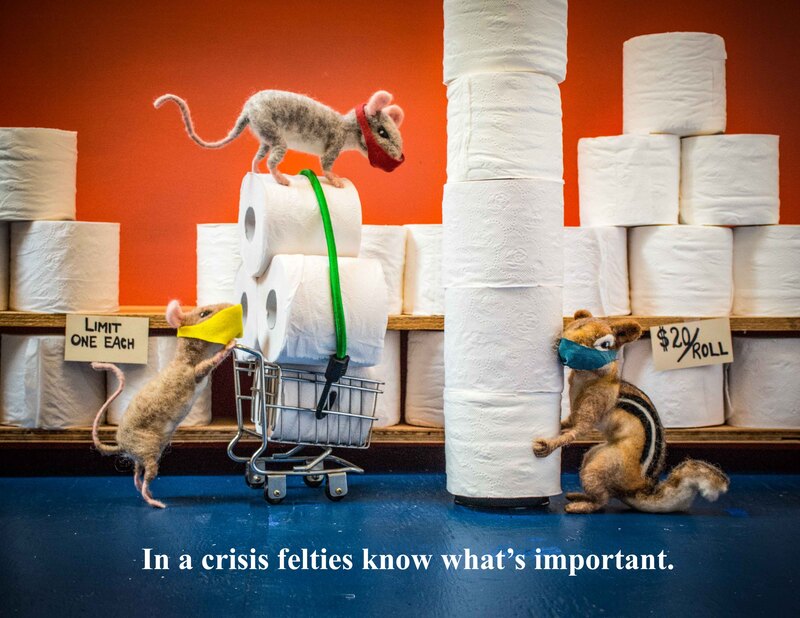

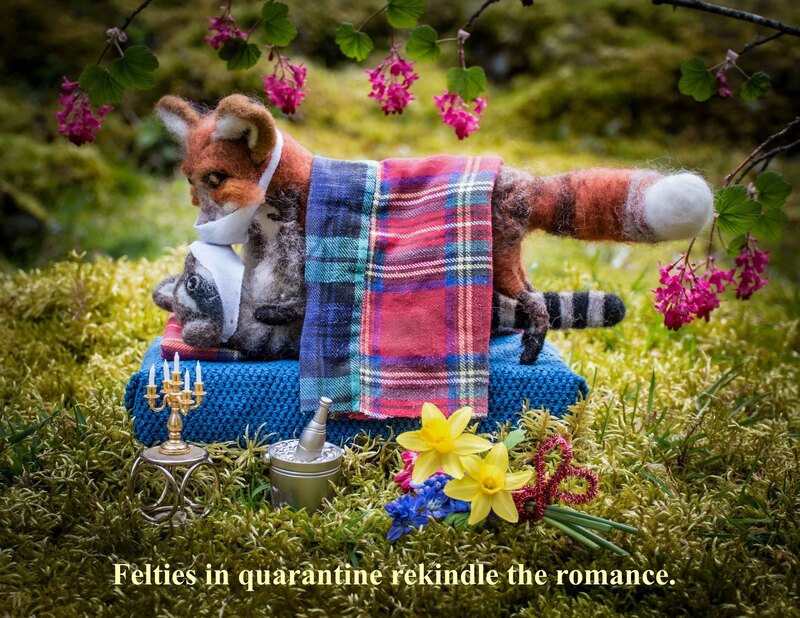

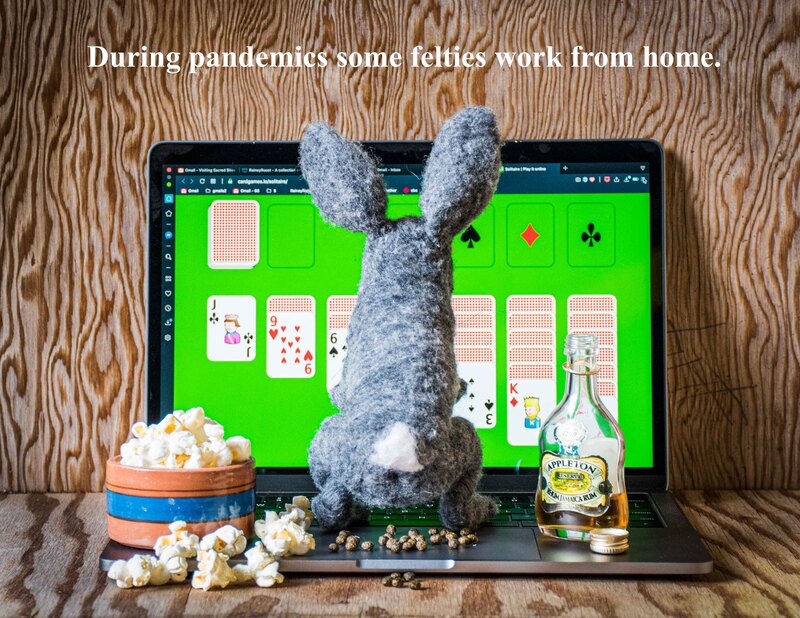

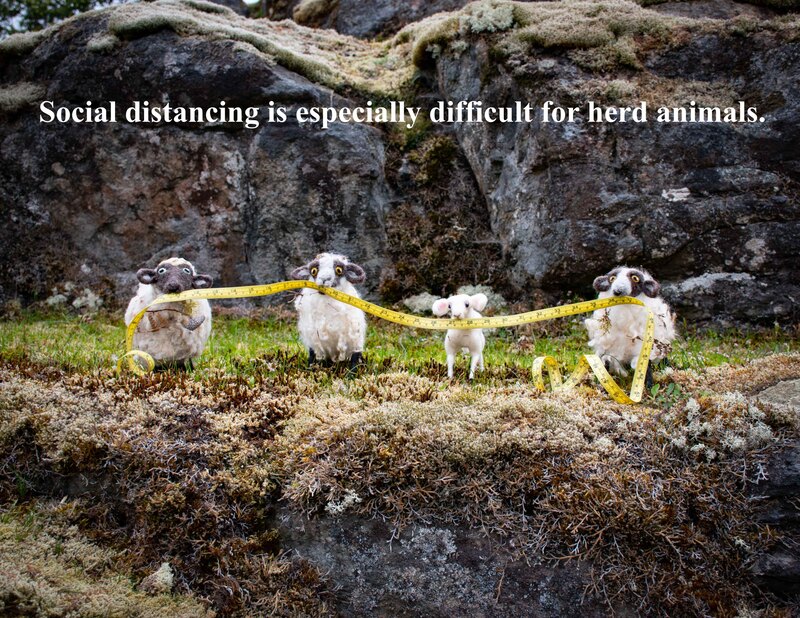

Who knew a 10 gram violet-green swallow could enslave a human for 18 days. It was not a conscious decision to give up my freedom to care for this gaping maw? There was no getting him back into the nest in the neighbour’s roof. His siblings died in the heatwave, but Chipikins abandoned ship, hoping for a better fate. I brought home the barely feathered swallow only so he could die more comfortably than in the dust and sun. I meant to put him on moss in shade. I was too busy for this responsibility. I have fostered birds in need before, so I have a mealworm colony for such occasions. This was the fatal error. I should not have fed him a mealworm. He wanted more. I gave him more. 18 days later I was still feeding him. I did not go out during this time because Chipikins had to eat every 25 minutes. I attracted flies to swat for food. I beheaded mealworms. I made nests and a flight cage. It was longer than a covid quarantine. What was I thinking? Oh yeah, I wasn’t. Chipikins was maybe a week old in the photo below, and just getting feathers. Canned cat food on a chopstick was part of the diet. Baby birds cannot swallow at first. The food must be delivered directly to the stomach. Bugs could be pushed in with my fingers. A sprinkle of ground egg shell in the food added calcium. For a week Chipikins lived on the counter. A baby bird takes 23 days to grow up and fledge so the changes came fast, in body as well as mind. One morning I awoke to a different bird. He had longer wings. He became engaged in the world, made eye contact, soaked in his surroundings. Before that he ate and slept. That’s all. By the second week it was time to make a flight cage. I would have let Chipikins be free to explore the house, but on his first clumsy attempts to fly he bonked into the windows, so I had to contain him. I would have learned more about his personality if he were free to roam, show his interests, and engage with me. He didn’t mind the pen, but at feeding time he would wiggle out in excitement. There is a video of chow time at the end of this post. By day 18 it was time to send Chipikins to the sky. I filled him with mealworms and flies first. When I opened my hands outside he zoomed over the bluff and was gone. I thought that was anticlimactic. Swallows eat only in flight. He wasn’t able to feed himself yet and needed my help, but an hour later he was back and talking to me from high in the trees. He would circle around me expertly, doing figure eights, then back to perch in a fir tree. All day I knew where he was because he’d answer when I spoke. “Hey human, I’m in this tree.” “Hey human, now I’m over here.” Through binoculars I saw him preen and bask in the sunshine. His chirps were happy. He was not in distress. Then a miracle. His parents, who I thought were long gone after his siblings died, visited him in his tree. It was only for a moment. They came again later in the day, and Chipikins flew up to meet them briefly. They left, and he perched again. In the early evening he was gone. I knew this because he did not answer me. The next morning I was calling when 3 swallows flew high above. One zoomed down to tree top level and said hi. Later in the day the 3 swallows passed over again and Chipikins came right down to circle me, chatting away, telling the story for me to translate. My neck was sore from 2 days of looking up. Often I thought I saw Chipikins in the sky and I called out, but it was a floater in my eye. The following 2 pictures are not mine. They are examples of what Chipikins was, and what he will become when he matures into his colours. I believe he is male. That these helpless aliens can grow to independence in 3 weeks is a friggin’ miracle. This story has the best possible outcome, and I know he will be okay. My bondage was not in vain. Soon he will fly to California or further south for the winter. This swallow family returns each year to nest. I wonder if Chipikins will say hi. I will build a nest box in the peak of my ceiling, through the wall on the north side of the house. From my sleeping loft I will watch through a two way mirror if the family chooses this for a home. Good bye, Chipikins. Good luck. Write when you find work. And they all lived happily ever after. I live in a wildlife blind. I sit before these three tall windows and watch. A hawk snatched a junco at the window bird feeder four feet from my eyes. Owls watch from the trees. Frogs live in the lobelia planters hanging off the house. Feral sheep fertilize the moss. There are deer, chickens, raccoons, flutterbies, huckleberries, birds galore… The nubbly texture of the mossy bluff, and its various levels and shapes and stages, is a stimulating view. The problem is, only I get to see it. I tell people of the magic in this pulchritudinous (beautiful) yard, but how are they to imagine it? It is teeming with life. There is always movement. It is ever changing. This slideshow shares the magic I see through just these three windows, plus a few shots from the glass door beside them. Crank up the volume. The soundtrack is the birdsong I hear whilst I stare and stare and stare. It turns out the felty community is also affected by the pandemic.

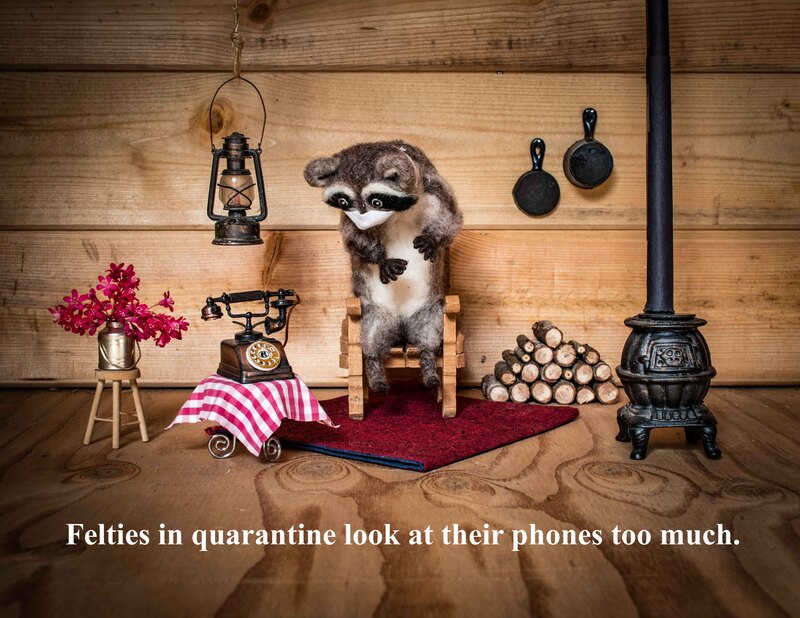

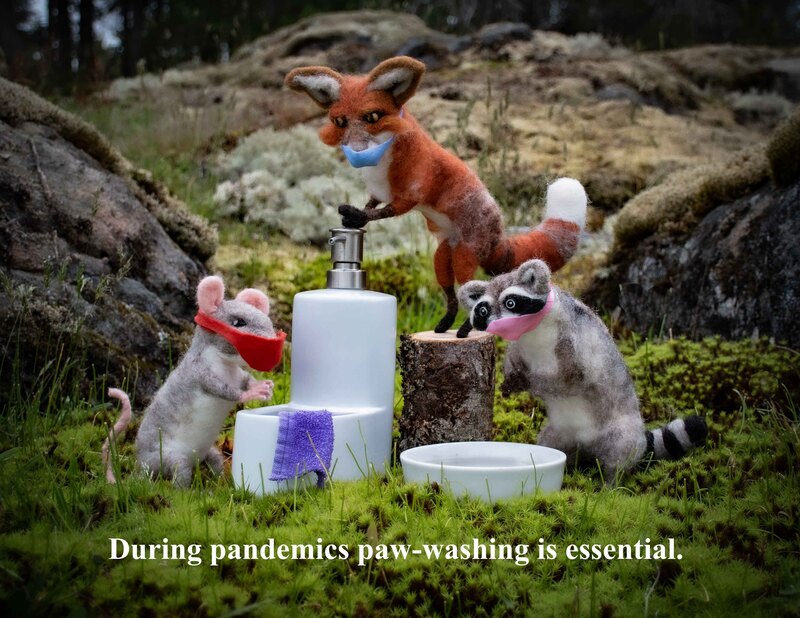

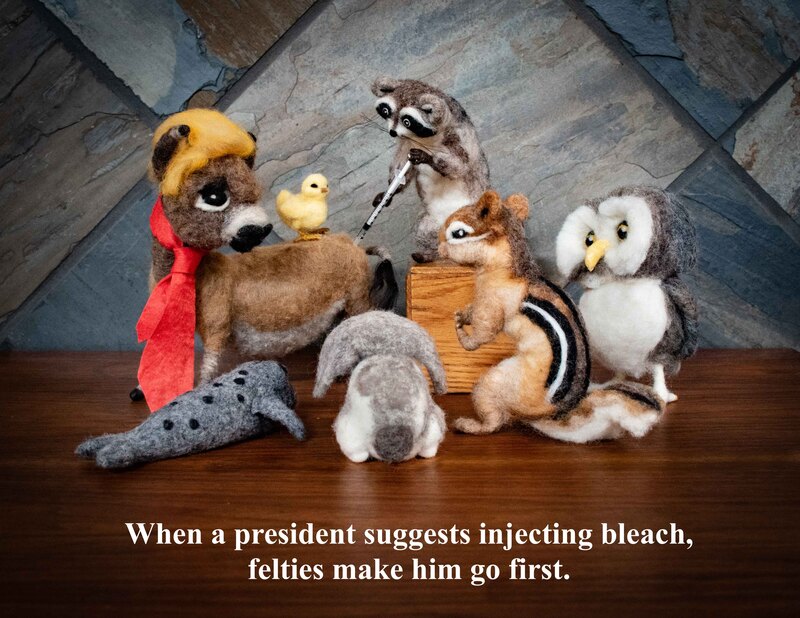

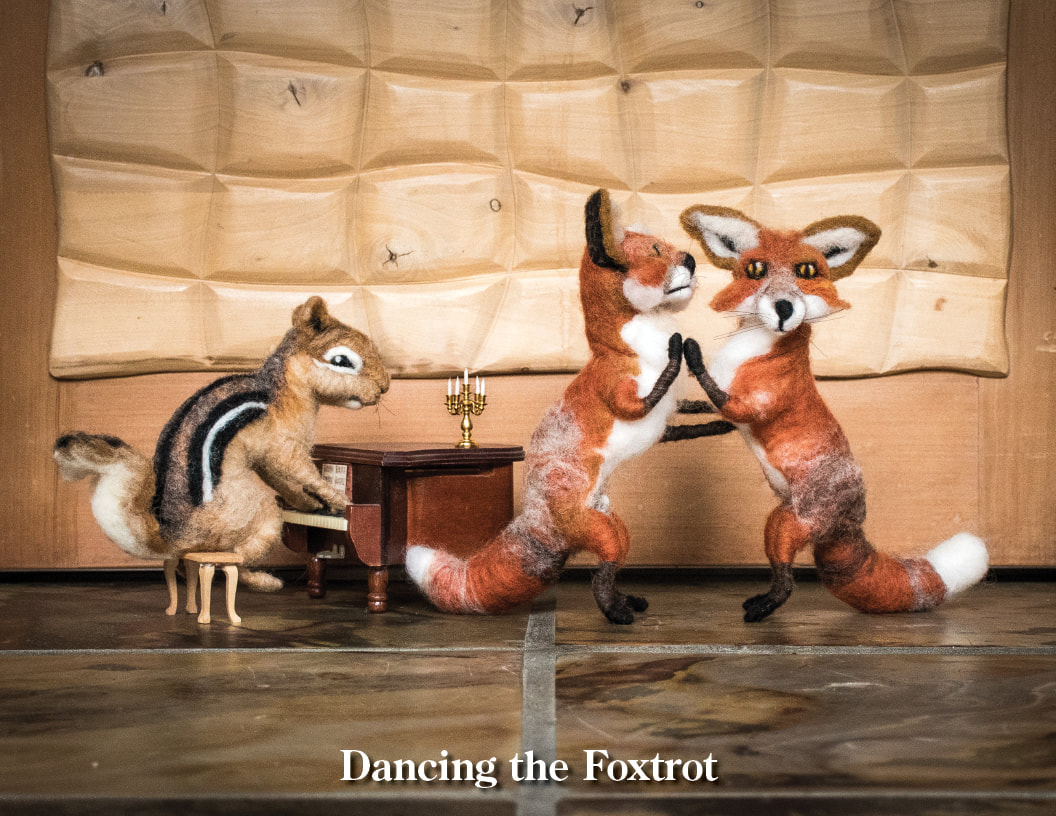

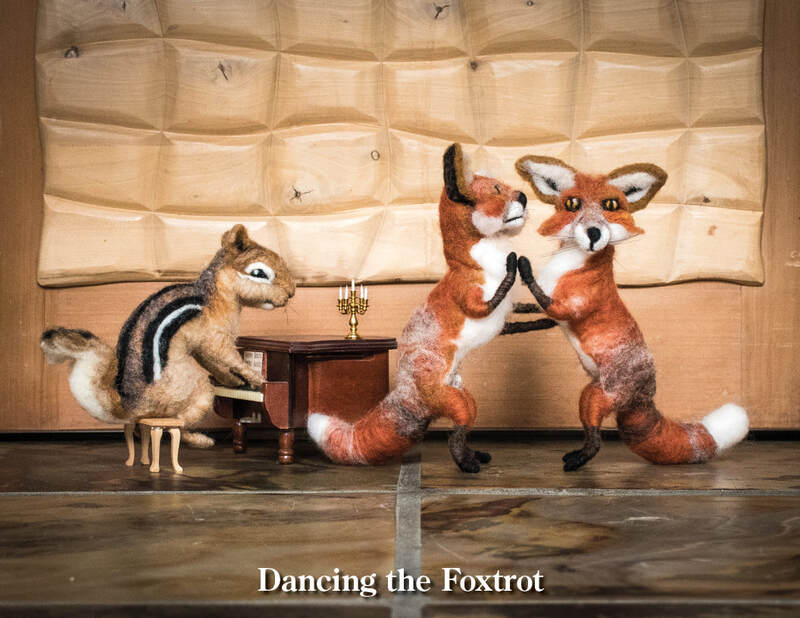

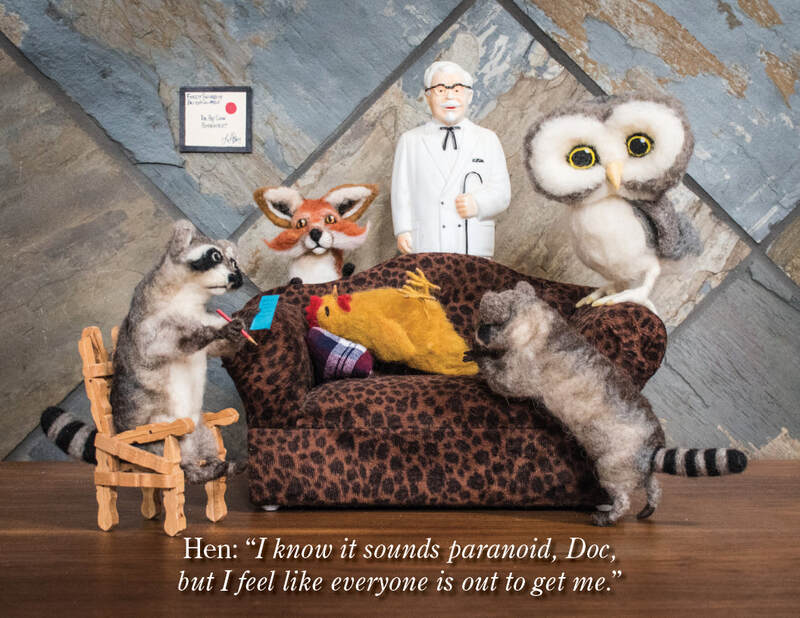

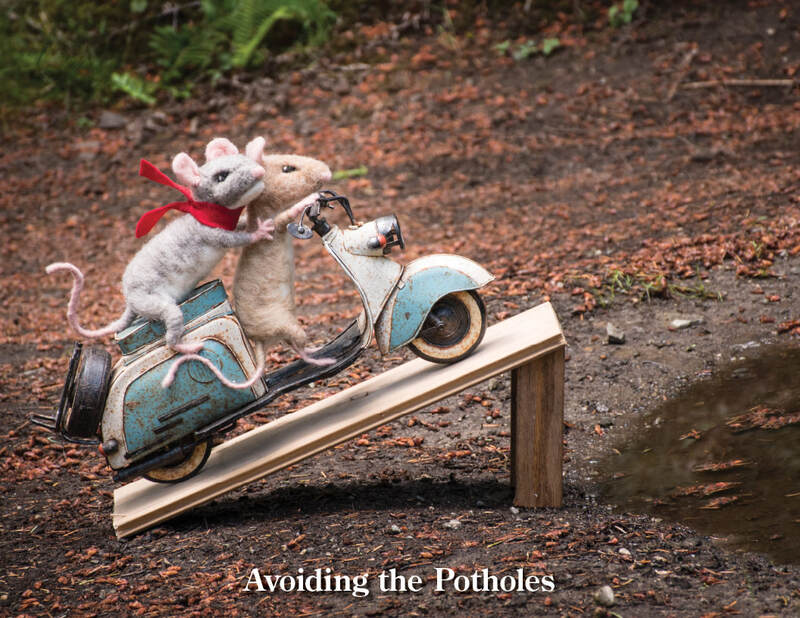

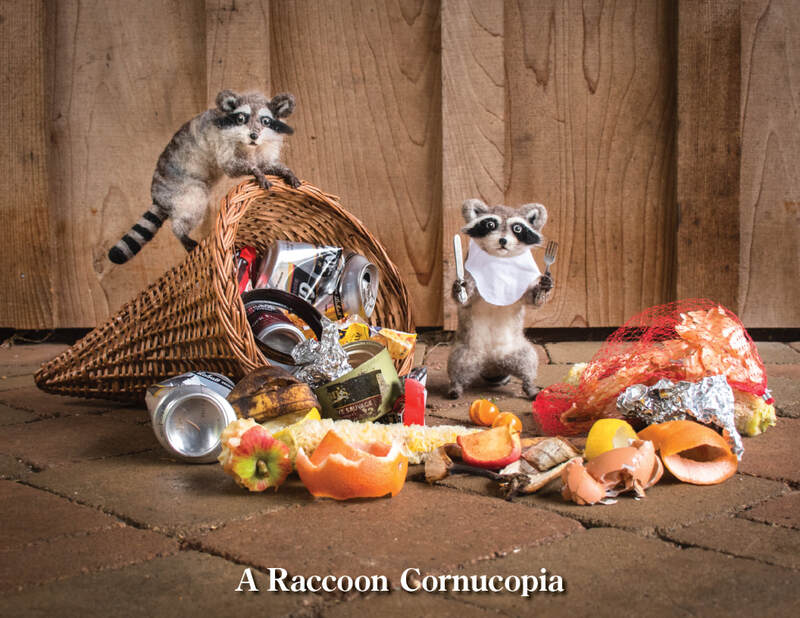

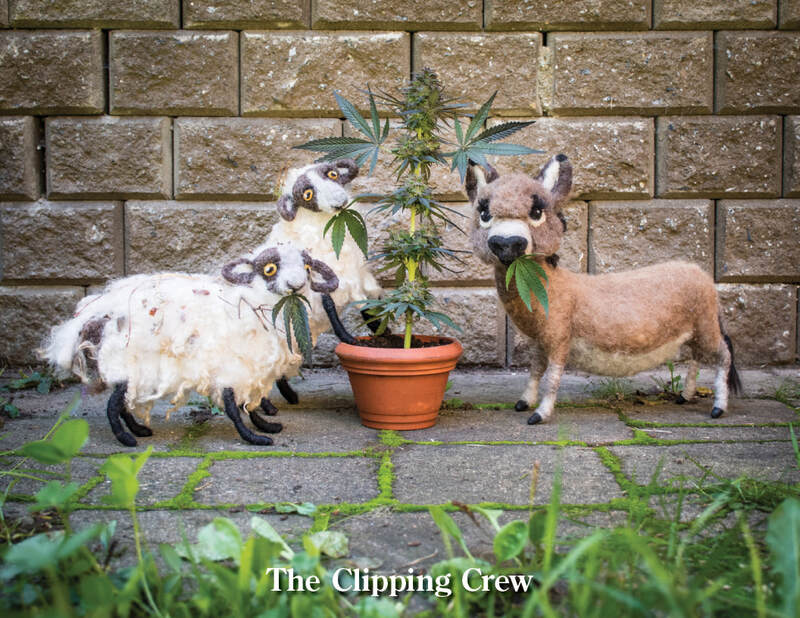

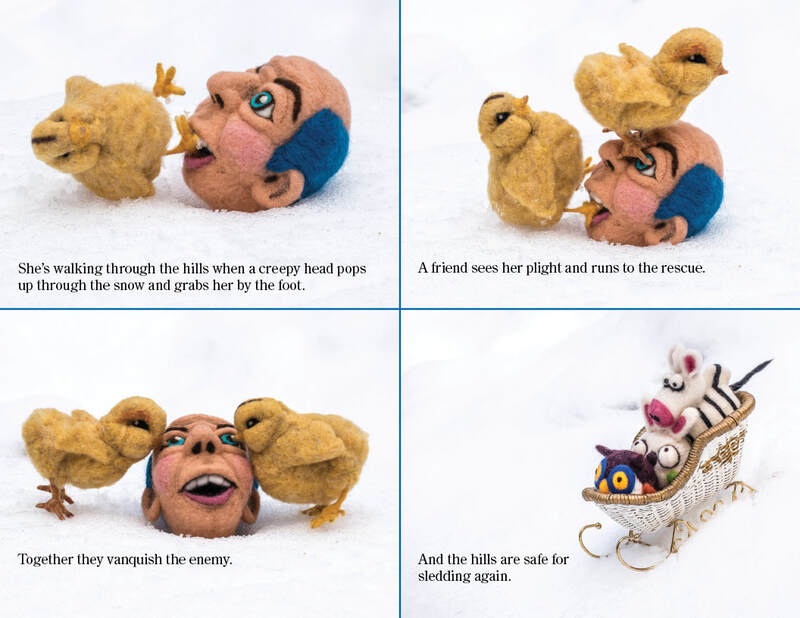

Felties are made of wool and wire. When I finish a creation, it comes to life like Pinocchio, then fledges into the world to be among its own kind. Felties are a species unto themselves. I have been studying their society through binoculars. By employing some clever disguises, I was finally able to get close with my camera. In this series, Felties in Lockdown, I have documented some of the ways the elusive felty community is handling the pandemic. 2021 Calendars are available for $20 each. Over the seasons friends oozed, hopped, flew, crawled or slithered by for tea. We had enchanted tea parties in this magical yard. Their manners were charming, except for Ms. Toad who peed on my hand as I was helping her be seated. She had a pre-existing bladder disorder so I didn't take it personally. The woodland guests came to my home. The ocean dwelling friends invited me to theirs on the stony shores of the Salish Sea. Each one sat for a portrait.

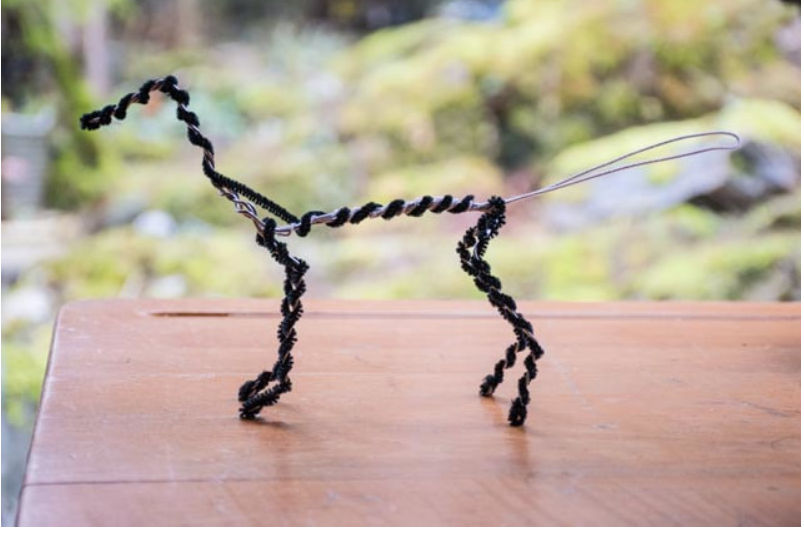

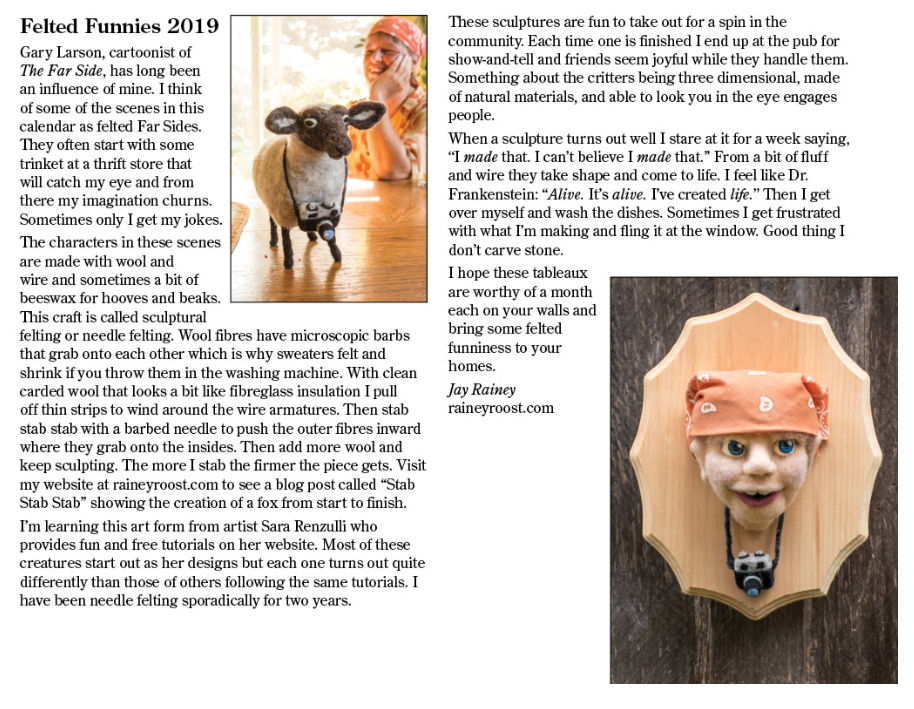

As a tea snob I like black, loose leaf, organic, fair-trade, free-range, non-gluten, shade-grown, CFC free, no MSG, vegan, dolphin friendly, Earl Grey tea. Some guests preferred we share a pot of fresh picked mint tisane. Two chose an earwig infusion. It was slightly bitter. My gratitude to Mother Nature, who nurtures these delicate little wonders. Long may she reign. These foxes are made of wool and wire. This craft is called sculptural felting or needle felting. Wool fibres have microscopic barbs that grab onto each other which is why sweaters felt and shrink if you throw them in the washing machine. With clean carded wool that looks a bit like fibreglass insulation I pull off thin strips to wind around the wire armatures. Then stab stab stab with a barbed needle to push the outer fibres inward where they grab onto the insides. Then add more wool and keep sculpting. The more I stab the firmer the piece gets. I'm learning this art form from artist Sara Renzulli who provides fun and free tutorials on her website. Most of these creatures start out as her designs but each one turns out quite differently than those of others following the same tutorials. I have been needle felting sporadically for 2 years. Here is a fox from start to finish. First the raw materials. Then a wire armature. It is wound with pipe cleaners to make the wool hang on. These are felting needles with tiny barbs at the tips. (Pictured here with a human tooth for scale.) Wool is wound around the armature and stabbed with a barbed needle. More fibre is added to give shape and texture. Every breed of sheep has wool with different characteristics and several types are used in one sculpture. The coloured wool is added last. The shapes for the face are formed separately on the felting surface and then stabbed into the head and sculpted with the needle. The felting surface is foam so I can stab into that without breaking needles or jabbing my hand. And Voila! Foxes!

World War 2 has been an obsession of mine since my early memories. At 6 years old I dreamed of battlegrounds of burnt and broken trees and houses and men. Ten years ago I had the following dream that has stayed with me. I wrote it down when I awoke. I have always remembered it but the details grew sketchy over the years. Last week while flipping through old journals I found it again. It was not surreal like so many dreams. It made sense and could have really happened. It was like a scene from a movie or novel. I thought of enlarging it into a story with added details from my imagination but I like it just as it happened.

I dreamed of a soldier in WW2. He was dirty and exhausted and lost but peace was called that day and he was slowly making his way through bombed out villages. He was alone in his battle gear and separated from his unit. He came upon an abandoned, shelled-out farmhouse. It was coming on night so he found himself a corner of a room upstairs, pushed aside the fallen plaster and glass and put out his blanket. He had a transistor radio and with an earphone listened to the armistice. He kept his rifle handy in case there were Germans around who didn't know they could stop killing each other now. Then downstairs he heard sweeping. He sneaked to the top of the stairs with his rifle loaded with his last two bullets. He peaked around the corner and the farmer who had lived there had come home, trying to make some sense of his crumbling house. The soldier waved and they spoke. That night two more soldiers arrived, also lost and making their ways toward the beaches to find their units. A mother and her girl arrived looking for shelter. They pushed aside more rubble and glass and all laid out their blankets and pooled their food. Someone had bread, another had cheese. There were some army rations and a chocolate bar. An unbroken bottle of wine was found in what was left of the farmhouse pantry. They talked quietly. They were not jubilant or celebratory, just worn out and ready to go home. Then the first soldier saw behind a broken wall an undamaged banjo, tuned it, and in the flickering candlelight with this group of tired stragglers he played, almost sadly, "Ode to Joy." After this dream I woke up, put on my army helmet, carried my banjo to the top of the bluff, and played "Ode to Joy" to the Salish Sea. This junco dad (right) is raising a much bigger cowbird baby. Cowbirds are called brood parasites because the mother will lay her egg in another species nest, displacing a host egg, then disappear and let the foster parents do all the work. A cowbird egg usually hatches in less time than other birds and the baby gets bigger faster and starves out the other nestlings. The junco dad in these pictures has been feeding this fledgling for a week, as well as the weeks it was in the nest. He is getting tired of the constant pestering for food. Although he takes his responsibility seriously and continues to feed, he occasionally takes a lunge at the baby. The cowbird should be self feeding by now but there is a problem - the upper mandible is too short. It stops just after the nostrils. He can't pick up seeds. It's like eating with one and a half chopsticks. I've been waiting to see if he would adapt and figure out some other workaround but so far begging is his main solution. There is seed on the ground as well as the feeders and yesterday he learned that it is easier to eat from the ground than from the hard surface of the feeders because he can push his lower beak in a bit until the upper mandible can grab a grain of millet, so he is adapting. The father, after a week, has stopped feeding him and now the cowbird must figure out how to live life with this mutation. Although cowbirds have a bad reputation and people dislike them, I can't blame the baby for the negligence of the parents, although I know this bird will grow up to copy the behaviour that is so frowned upon. Other species of birds rob nests and eat other birds and we don't think they are terrible. I think with cowbirds we put our own social mores on them. They are not monogamous and they do not stick around to raise their young so we judge them. They used to follow the buffalo herds and were transient so they couldn't stay in one place long enough to raise a brood. Snubby is alive and at my feeder and is interesting. I'm not going to wring his neck so I may as well enjoy him. And I got a blog post and a few of decent photos out of this cowbird's dilemma and his long suffering junco dad. -several days later- Snubby is eating seeds from standing grass. I sprinkle food on the ground for him. He hangs out with the chickens now and is not afraid of me, probably because he was raised just four feet away from me at my window feeder so he is used to my movements. He's always around and looks me in the eye while I talk to him. He spotted his dad today and went to him begging but got chased off. The dad has cut the cord and Snubby is on his own. He looks like a female at this point but they usually do when they are young so it's hard to tell. I will continue to call it a he. -another day passes- I am now under constant surveillance. At 6am there his is peering in the window. I go outside and he follows two feet behind. I am accompanied to the outhouse. Yesterday I was napping in my reclining lawn chair and Snubby perched on my knee. He flies from window to window following my movements through the house. He is too short to see in the door so he stands on the step and jumps up to window level again and again like he's on a trampoline. This is all because I tossed him three meal worms yesterday. Since then he has had about 15 more. I'm rationing them because he needs to find food on his own and also the meal worms will run out and I am afraid he will then feast on my eyeballs. He waits on a shelf by the door outside and when I open the door there he is ready for his treat. He learned so fast. Birds are such sharp cookies. - next day - A cat killed Snubby. Broke my heart. On Easter Monday my older house rabbit died. Buzz was my companion in the house for 8 years. She used a litter box and didn't chew wires, though she did eat the tassels off the rugs. She was an excellent companion and each time I looked at her a hundred times a day I'd get a surge of pleasure. I miss her gentle spirit around the house and her enthusiasm for treats. She loved to shred phone books and devour boxes. Buzz is survived by fellow rabbit, Beasty Wieners, who is seven.

I used to have a mattress on the floor where I slept and both rabbits slept with me. Waking up to bunnies in the bed is funny. I'd scrunch over to the one side so they could use the bed as a runway and they charged full speed up and down, leaping and twisting in the air like little lambs. It's a fun way to wake up - if it weren't 4:00 in the morning. Buzz was a lionhead rabbit, a smallish breed with short body hair and a mane of longer fur around the head. Her mane wasn't pronounced because Beasty ate it. She also ate all her whiskers. Beast always kept Buzz well groomed and trimmed. Even on Buzz's last day Beasty Wieners spent much of the day grooming her. I knew she was in good hands. Buzz had a fairly peaceful death. She seemed to want my attention and I'm glad she didn't hide. She ate dandelion greens right up to the last day when hand fed and was even dragooned into a short game of chase by the Beast on her second last day. When the time came she scurried into her tunnel and died there. This breed lives 7 to 10 years so she was in her golden years. Because of this and because of the stress of the noisy ferry ride which would terrify her with all the dogs and strangers and commotion I felt it would be kindest not to subject her to any heroics at the vet when likely nothing could be done anyway. Buzz and Beasty Wieners were spayed which makes it easier to litter train, and makes them less likely to fight with each other. Introducing rabbits is tricky, you could have a bonded pair or a fight to the death. You need neutral territory so when I introduced Beast to Buzz 7 years ago I used my neighbour's entryway and sat wearing oven mitts and gumboots and holding a broom for over an hour, prepared to intercept if the fur should fly. Buzz was aggressive at first but was asserting her dominance. Beasty just wanted to eat the broom. Eventually they turned their backs on each other and groomed and I knew it was a match. I took them home where they were inseparable and over the next 7 years their bodies were almost always touching. They especially enjoyed sprawling by the fire in winter, and lying in sunbeams in the summer awaiting raisin deliveries. Lionhead rabbits shed like huskies and I save up the fur every winter. In spring I put it on a rocky outcropping in front of my window. Soon chickadees and yellow-rumped warblers come for the fur to line their nests. It's the only time I see these birds up here but they come for this bit of fur every spring. This year after Buzz died I put out the fur I'd collected over the winter and the birds came and gathered great wads of it in their beaks. I like to think of those cozy chickadees in their fur lined nests. Buzz was a bright and gentle spirit and it seems fitting she should live on in this way. Here is a picture of Buzz snoozing in her litter box. |

AuthorJay Rainey is an artist living on an island in British Columbia, Canada. Archives

October 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed